But this is merely Perception establishing its character. The Deep End is showing that, despite her disability, Cassie is far from helpless in the situation. She explores the house confidently and is equipped to deal with more or less any situation on her own. At the same time, it’s offering the player a chance to acquaint themselves with Cassie’s unique way of interpreting the world before it turns the screw.

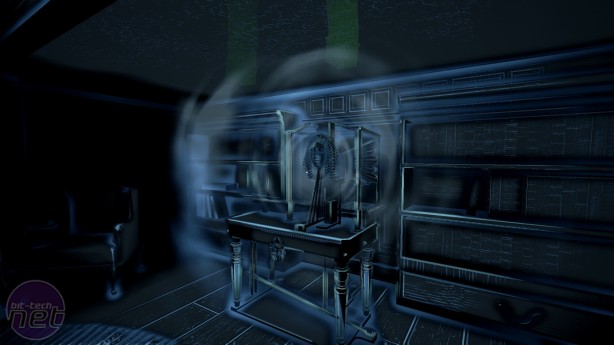

Perception’s story is split into four chapters, each of which drags you farther back into the mansion’s past. As you progress, Cassie’s audio/visual aids are stripped away, while the layout of the house become increasingly unpredictable. Cassie’s visualisation of the house begins to include visions of the house’s past and even memories of events that occurred hundreds of miles away from the building itself.

It’s some superb level design, constantly throwing off your bearings but without fundamentally changing the layout of the house and leaving you completely disoriented. As well as being more surreal, the later levels are more dangerous as well. The third chapter in particular introduces some particularly disturbing and deadly enemies that I think will be talked about at some length after the game’s release.

While Perception has moments of high tension and a few effective jump-scares (along with some less effective ones), the core of its horror lies in the stories it tells about the house’s previous inhabitants. The writing and voice acting are both of exceptional calibre, sharp, vivacious, and evidently heartfelt. I don’t want to reveal too much about the plot, but I’m going to detail one of its stories as an example. If you don’t want to know even that much, skip the next two paragraphs.

The second chapter takes Cassie back to the second World War and charts the story of a woman named Betty, whose husband Gene is in Europe fighting in the trenches. Betty is evidently a strong-willed individual, but she also comes across as quite cold and priggish, almost matronly. In addition, she’s weirdly obsessed with bringing her father’s pistol across the Atlantic to Gene, because she believes the army-issued weapons won’t be sufficient to protect him.

Basically, we’re set up to think of Betty as cold, probably mad, and possibly even worse than that. But what is gradually unveiled as Cassie explores this iteration of Echo Bluff is Betty’s unconditional love for her husband and the strength of her resolve as she tries again and again to get herself shipped across the Atlantic just so she can ensure Gene is safe. It’s a powerful and touching little story, and it’s not the only one that Perception contains.

What Perception does is use standard horror tropes to subvert your expectations about the characters whose pasts you explore. Its horror is one of small mistakes and simple misjudgements which lead to terrible consequences, and these events are far more terrifying than anything other recent horror games like Outlast II or Little Nightmares could conjure. It’s also emotionally arresting and at times genuinely heartbreaking. It’s not perfect; there’s the odd duff line and moments where it lays on the pathos a touch too thickly. But as a storytelling game, Perception is far stronger than I anticipated.

That said, Perception does suffer from a couple of more substantial problems. You may have noticed that I haven’t mentioned the Presence since the third paragraph. This is because, ironically, the Presence isn’t that much of a Presence in the game. The idea is if you make too much noise while exploring, the Presence will start hunting you. But aside from scripted encounters, this only occurred once in my entire playthrough, and only because I deliberately provoked it, battering the environments with my cane like I was facing down JK Simmons in the finale of Whiplash. In short, Perception is way too generous in letting you avoid the Presence, and consequently a major mechanic of the game is criminally underused.

This isn’t the only example of Perception undercooking a good idea either. Cassie has a couple of neat tools at her disposal to help her interpret the world around her. Delphi is a text-to-speech app that reads out text of anything you photograph, while Friendly Eyes is another app that connects Cassie to a remote user who will describe any photograph she sends. Ultimately, though, these function as cleverly disguised audio-logs, rather than being implemented in a more dynamic fashion. I would have preferred it if Cassie’s phone was a persistent tool that you used to interact with the game world, rather than being a context-sensitive action only available in specific circumstances.

The end result is that at times Perception can feel quite static, lacking the dynamism of horror games like Amnesia and Alien: Isolation. But it makes up for this in so many other ways - the execution of its concept, the stunning art and level design, and those elegant and soulful stories - that such flaws are easily forgiven. Its experience has lingered in my mind far longer than any other horror game I’ve played this year. Play it.

Perception’s story is split into four chapters, each of which drags you farther back into the mansion’s past. As you progress, Cassie’s audio/visual aids are stripped away, while the layout of the house become increasingly unpredictable. Cassie’s visualisation of the house begins to include visions of the house’s past and even memories of events that occurred hundreds of miles away from the building itself.

It’s some superb level design, constantly throwing off your bearings but without fundamentally changing the layout of the house and leaving you completely disoriented. As well as being more surreal, the later levels are more dangerous as well. The third chapter in particular introduces some particularly disturbing and deadly enemies that I think will be talked about at some length after the game’s release.

While Perception has moments of high tension and a few effective jump-scares (along with some less effective ones), the core of its horror lies in the stories it tells about the house’s previous inhabitants. The writing and voice acting are both of exceptional calibre, sharp, vivacious, and evidently heartfelt. I don’t want to reveal too much about the plot, but I’m going to detail one of its stories as an example. If you don’t want to know even that much, skip the next two paragraphs.

The second chapter takes Cassie back to the second World War and charts the story of a woman named Betty, whose husband Gene is in Europe fighting in the trenches. Betty is evidently a strong-willed individual, but she also comes across as quite cold and priggish, almost matronly. In addition, she’s weirdly obsessed with bringing her father’s pistol across the Atlantic to Gene, because she believes the army-issued weapons won’t be sufficient to protect him.

Basically, we’re set up to think of Betty as cold, probably mad, and possibly even worse than that. But what is gradually unveiled as Cassie explores this iteration of Echo Bluff is Betty’s unconditional love for her husband and the strength of her resolve as she tries again and again to get herself shipped across the Atlantic just so she can ensure Gene is safe. It’s a powerful and touching little story, and it’s not the only one that Perception contains.

What Perception does is use standard horror tropes to subvert your expectations about the characters whose pasts you explore. Its horror is one of small mistakes and simple misjudgements which lead to terrible consequences, and these events are far more terrifying than anything other recent horror games like Outlast II or Little Nightmares could conjure. It’s also emotionally arresting and at times genuinely heartbreaking. It’s not perfect; there’s the odd duff line and moments where it lays on the pathos a touch too thickly. But as a storytelling game, Perception is far stronger than I anticipated.

That said, Perception does suffer from a couple of more substantial problems. You may have noticed that I haven’t mentioned the Presence since the third paragraph. This is because, ironically, the Presence isn’t that much of a Presence in the game. The idea is if you make too much noise while exploring, the Presence will start hunting you. But aside from scripted encounters, this only occurred once in my entire playthrough, and only because I deliberately provoked it, battering the environments with my cane like I was facing down JK Simmons in the finale of Whiplash. In short, Perception is way too generous in letting you avoid the Presence, and consequently a major mechanic of the game is criminally underused.

This isn’t the only example of Perception undercooking a good idea either. Cassie has a couple of neat tools at her disposal to help her interpret the world around her. Delphi is a text-to-speech app that reads out text of anything you photograph, while Friendly Eyes is another app that connects Cassie to a remote user who will describe any photograph she sends. Ultimately, though, these function as cleverly disguised audio-logs, rather than being implemented in a more dynamic fashion. I would have preferred it if Cassie’s phone was a persistent tool that you used to interact with the game world, rather than being a context-sensitive action only available in specific circumstances.

The end result is that at times Perception can feel quite static, lacking the dynamism of horror games like Amnesia and Alien: Isolation. But it makes up for this in so many other ways - the execution of its concept, the stunning art and level design, and those elegant and soulful stories - that such flaws are easily forgiven. Its experience has lingered in my mind far longer than any other horror game I’ve played this year. Play it.

MSI MPG Velox 100R Chassis Review

October 14 2021 | 15:04

Want to comment? Please log in.